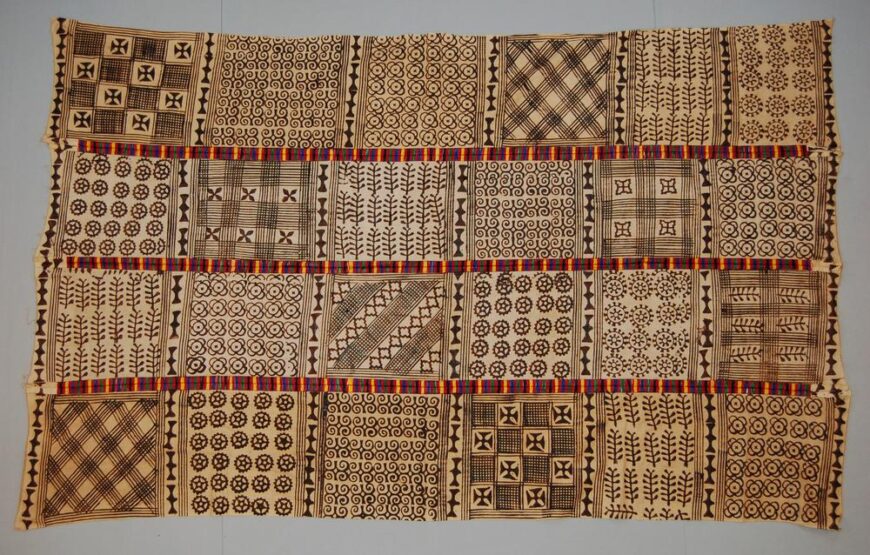

Cloth, 1968 (Asante people), stamped and embroidered cotton, 221 x 140 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Cloth is a versatile medium. Besides serving practical purposes, such as covering its wearers, cloth can be used to communicate or conceal a variety of messages related to one’s identity, including social and economic status, gender, political views, and cultural, ethnic, or religious affiliations.

Among the Asante people of Ghana, adinkra and kente cloth are associated with royalty, since it was initially deemed the exclusive property of the Asantehene (the title of the Asante monarch). Over time, the restrictions surrounding who could wear adinkra and kente cloth were relaxed, and today, anyone who can afford to purchase the cloth can wear it. While adinkra and kente cloth can both be worn during important occasions, adinkra cloth is associated with mourning and is worn primarily at funerals. Adinkra cloth is also distinguished from kente (where patterns are woven) in that its patterns are stamped on the cloth. Adinkra cloth gets its name from adinkrasymbols, which convey values, such as wisdom and unity held by the Asante people. Adinkra symbols often reference proverbs and can be named after significant figures, entities, and events.

The adinkra cloth above (which appears beige but was white originally) showcases a variety of adinkra symbols that have been stamped onto the cloth. Divided into twenty-four squares, each square contains repeating adinkra symbols.

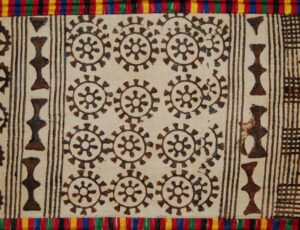

Cloth (detail), 1968 (Asante people), stamped and embroidered cotton, 221 x 140 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Adinkra stamp, possibly referencing the Donnodrum and unity, 20th century (?), gourd, wood, cotton, and hessian, 3 x 6 x 0.8 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Each square is separated on its left and right sides by a repeating motif that resembles an hourglass shape with two triangles protruding out at the center. This motif creates six columns of squares and also adorns the left and right borders of the cloth. This too is also an adinkra symbol.

Cloth (detail), 1968 (Asante people), stamped and embroidered cotton, 221 x 140 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Furthermore, the cloth is divided into four rows by brightly colored stitching called nhwemu. This stitching, which appears in blue, red, green, black, and yellow bands, is used to attach smaller strips of cloth to produce a larger piece.

Weaving sample featuring the widely-recognized adinkra symbol, Gye Nyame, late 20th century (Asante people), woven, dyed, and printed cotton, 29.5 x 15 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

In this weaving sample, we see one of the most widely-recognized adinkra symbols, Gye Nyame, which means “(I fear no one) except God.” It has an “S” or “Z” shape with two parallel lines in the middle and two additional lines sticking out at the top and bottom of the symbol. According to the scholar Boatema Boateng, Gye Nyame originally referred to someone’s courage, but has been adopted by Ghanaian Christians to signify their faith in God and God’s power.

The sample also contains the adinkra symbol, sankofa, which is represented in two forms: as a heart (in the upper right corner of the cloth) and as a bird turning its head back to look behind (in the bottom left corner on the black piece of the cloth). The value expressed by sankofa is wisdom, alluding to the proverb or advice to reflect and learn from the past to prepare for the future.

It is important to note that the names and meanings of adinkra symbols are sometimes contested. During conversations with adinkra cloth makers at Asokwa (the town where adinkra cloth originated), Boatema Boateng found that they did not recognize some of the symbols she showed them, or that they did not agree with her on some of the names of the symbols.

Cloth borne out of defeat

Among the Asante people, there are different accounts (and variations of those accounts) of the origins of adinkra cloth. One popular account traces the cloth’s origin back to 1818, when the Asante people of Ghana captured and defeated Adinkra, the King of Gyaman. When the king was killed, it is said that he was wearing cloth (that has come to be known as adinkra cloth) to express his sadness over his defeat and deaths of his soldiers. One version of this account notes that in order to be spared the same fate as his father, the king’s son had to teach the Asantehene’s cloth makers in the town of Asokwa how to create this cloth. Another iteration says that when the King of Gyaman was defeated, some of his cloth makers were taken to work for the Asantehene. [4]

Another account suggests that the origin of adinkra cloth is much earlier, dating back to the Asante victory over the Denkyira, a kingdom that preceded the Asante. When Denkyira was defeated in 1701, cloth makers from Denkyira arrived in Asokwa and started to make adinkra cloth there.

In both of these accounts, the production of adinkra cloth was adopted by the Asante people due to the Asantehene. The town of Asokwa remains the official supplier of the Asantehene’s adinkra cloth, however, another town, Ntonso, is now a more prolific center of adinkra cloth production.

Calabash adinkra stamps carved in Ntonso, Ghana, 2009 (photo: ArtProf, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Creating adinkra cloth

Adinkra cloth is generally made by men and created by applying stamps with adinkra symbols to fabric. These stamps are carved from cassava tubers or calabashes by specialists or adinkra cloth makers who use them. The photograph above shows a range of different stamps with adinkra symbols, which are portrayed as abstracted forms of flora, fauna, and everyday objects, such as drums, wheels, and combs.

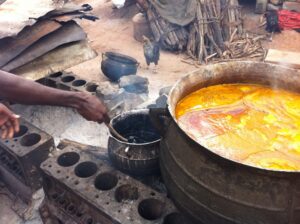

Adinkra stamp ink demonstration by the Boakye family in Ntonso, Ghana, 2010 (photo: shawnzam, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The black dye that is used to make adinkra cloth is referred to as badie, which is made of bark from the badie tree. The bark is soaked in water for a week, pounded, and then boiled with iron slag to produce a dark, dense liquid. Adinkra stamps are dipped in this dye and then pressed onto the cloth. When an adinkra cloth maker is finished stamping the cloth, he hangs it to dry.

Anthony Boakye prints an adinkra cloth with a calabash stamp in Ntonso, Ghana, 2009 (photo: ArtProf, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Wearing adinkra cloth

While adinkra cloth can come in different colors, the ones worn at funerals are usually blue or red. The word adinkra describes the process of saying goodbye to the departed, as it contains the Akan words, nkra (“message”), di nkra (“taking leave of someone”), and kra (“soul”).

The Asante chief wears adinkra cloth. Mary S. R. Sinclair, Ashanti (Asante) chief at the procession at Kumasi Sports Ground in mourning for King George V, 1936, gelatin silver print, 12.05 x 18.3 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Generally, men wear adinkra cloth by wrapping it around their bodies and over one of their shoulders, leaving the other bare. Women usually don adinkra cloth differently by wrapping it around their heads, their torsos, or their lower bodies.

While adinkra cloth is worn during funerals, Boatema Boateng notes that it is not worn during “the most intense periods of mourning.” [5] Instead, red ochre or black cloth, which is dyed by women, is worn during these deeply sorrowful times. This black cloth, called kuntunkuni, is not only used for mourning, but also for business-related matters at the Asantehene’s residence.

The old City Hotel was renovated and reopened as Golden Tulip Hotel in Kumasi, Ghana. The photograph shows the front view of the left wing of the building. On the building’s façade are adinkrasymbols, such as Gye Nyame in the upper left corner. The adinkra symbol, akofena, is to the right of the photograph underneath a sign that says the name of the hotel (which is obscured by the flags). Consisting of two swords that cross to form an “X” shape, akofena refers to power and authority. Golden Tulip Hotel, 2008 (photo: ZSM, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Embassy of Ghana in Washington, D.C. has adinkra symbols on its exterior wall. Embassy of Ghana, Washington, D.C., 2008 (photo: Bossi, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Beyond cloth: adinkra symbols on other forms

Adinkra symbols are not restricted to cloth. Besides being stamped onto fabric, they might be used for jewelry, such as bracelets and earrings, and other accessories. As the photographs above demonstrate, adinkra symbols can be used as decorative elements on buildings, such as the Golden Tulip Hotel in Kumasi and the Embassy of Ghana in Washington, D.C. Adinkra symbols also appear on the African Burial Ground National Monument in New York City, which was designed by Rodney Leon. Adinkra symbols, whether they are added on cloth, accessories, buildings, or monuments, are significant for their ability to convey the values and recall the histories of the Asante people.

SOURCE

Notes:

[1] Asante is also spelled Ashanti and Ashante in scholarship.

[2] Boatema Boateng, The Copyright Thing Doesn’t Work Here: Adinkra and Kente Cloth and Intellectual Property in Ghana (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), p. 22.

[3] Boateng (2011), p. 38.

[4] Suzanne Preston Blier, Royal Arts of Africa: The Majesty of Form (London: Laurence King Publishing, 1998), p.154.; Boateng (2011), p. 22.; Samuel Baah Kissi, Peggy Ama Fening, and Eric Appau Asante, “The Philosophy of Adinkra Symbols in Asante Textiles, Jewellery and Other Art Forms,” Journal of Asian Scientific Research, volume 9, number 4 (2019), p. 30.; Nii O. Quarcoopome, “Akan Ceremonial Cloths, Costumes, and Flags,” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts, volume 91, number 14 (2017), p. 61.

[5] Boatema Boateng, “Adinkra and Kente Cloth in History, Law, and Life” (presented at the Textile Society of America biennial symposium, Los Angeles 2014), p. 2.

Additional resources

Abraham Ekow Asmah, Vincentia Okpattah, and Effie Koomson, “Adinkra Cloth Production in Retrospect,” Africa Development and Resources Research Institute (ADRRI) Journal, volume 25, number 12 (2016), pp. 1–14.

Suzanne Preston Blier, Royal Arts of Africa: The Majesty of Form (London: Laurence King Publishing, 1998).

Boatema Boateng, “Adinkra and Kente Cloth in History, Law, and Life” (presented at the Textile Society of America biennial symposium, Los Angeles, 2014), pp. 1–10.

Boatema Boateng, The Copyright Thing Doesn’t Work here: Adinkra and Kente Cloth and Intellectual Property in Ghana (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011).

Samuel Baah Kissi, Peggy Ama Fening, and Eric Appau Asante, “The Philosophy of Adinkra Symbols in Asante Textiles, Jewellery and Other Art Forms,” Journal of Asian Scientific Research, volume 9, number 4 (2019), pp. 29–39.

Nii O. Quarcoopome, “Akan Ceremonial Cloths, Costumes, and Flags,” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts, volume 91, number 14 (2017), pp. 54–73.

Chris Spring, African Textiles Today (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2012).

Carol Ventura, “The Twenty-First Century Voices of the Ashanti Adinkra and Kente Cloths of Ghana” (presented at the Textile Society of America biennial symposium, Washington, D.C., 2012), pp. 1–12.

No comments:

Post a Comment