Historical styles dominated 19th-century architecture in the United States. American architecture, like the country itself, was young and wanted to connect to European historical styles that brought sophistication and cultural status to the new edifices of the United States. American vernacular architecture was made of wood—and to many, American architecture was anything but cosmopolitan. Among the most popular styles was the Classical revival which reinterpreted the forms of Greek and Roman architecture. The adaptation of Egyptian architecture, especially obelisks, as funerary markers and memorials was also widespread. Americans were used to seeing banks and financial buildings modeled on the ancient Parthenon, libraries that recalled the Pantheon, or an obelisk celebrating the legacy of a president, like George Washington.

There was also a limited revival of the architecture of the ancient Near East, which many scholars today call ancient Western Asia. In late 19th-century and early 20th-century New York City, the use of historical styles was often about finding a way to stand out from the crowd, to distinguish one’s building, business, or restaurant. These styles were exotic and different. The reception—the reinterpretation and adaptation—of ancient Assyria and ancient Western Asia enjoyed a brief moment of popularity in New York City, as we can see in four such buildings.

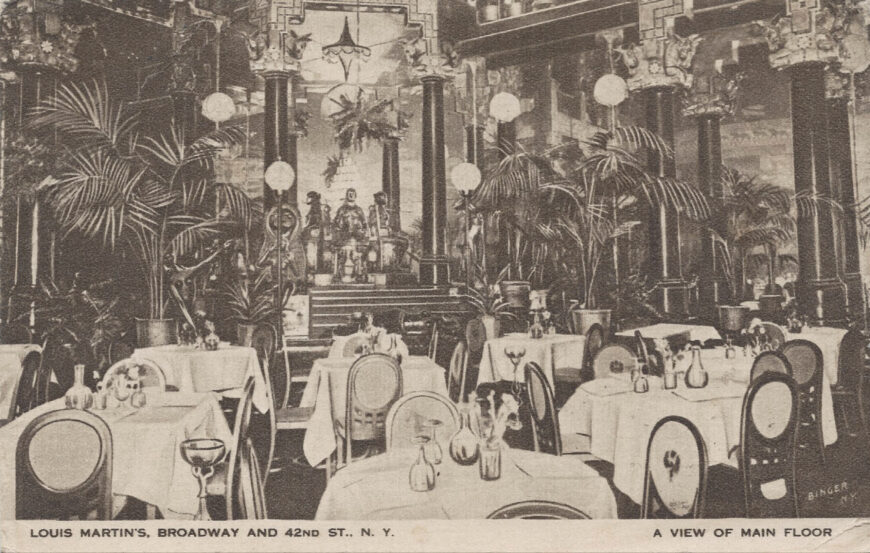

In the early 20th century, newly minted millionaires flocked to expensive, late-night establishments known as Lobster Palaces, where lobster and champagne were served after the theater. These restaurants competed with each other for deep-pocketed clients by creating over-the-top interiors.

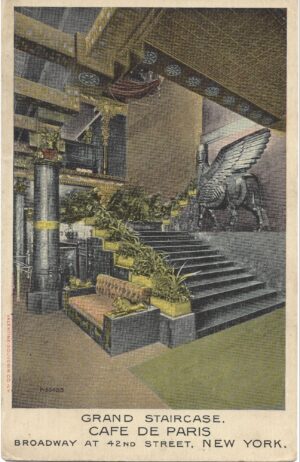

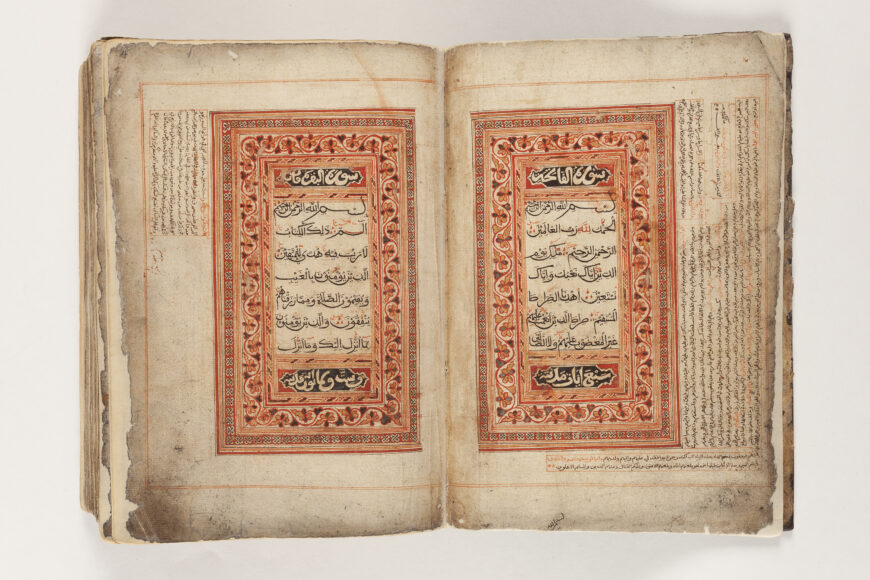

One of these Lobster Palaces known as Café de l’Opéra (at Broadway and Forty-Second Street) was remodeled in 1909. Its new décor reinterpreted and combined designs, art, and architecture from Assyria, Babylon, and Achaemenid Persian in one large mash-up of motifs from ancient Western Asia. According to The Architects’ and Builders’ Magazine, “Khorsbad (sic) or Perseopolis (sic) or an ancient Persian Tomb” inspired the main dining room which had three stories of seating around a central court with a fountain, whose central feature was a Mesopotamian ziggurat topped with an illuminated orb, tucked inside a pavilion supported by black marble columns. The capitals of these columns, rather than being decorated with Assyrian motifs, were actually replicas of the Achaemenid Persian bull capitals from the audience hall (apadana) of the palace of Darius I at Susa.

Painted lions, a central motif in the palaces of ancient Iraq and Iran, adorned the balcony landing. The monumental staircase was carpeted and flanked by pairs of gilded lions and colossal lamassu that rose to the balconies and upper floors, which The New York Times reported “was modeled after the famous staircase in the Temple of Persepolis.” A reproduction of the 1891 painting The Fall of Babylon by the French painter Georges Rochegrosse covered the lofty side wall of the main dining room. There was little interest in archaeological accuracy—rather the appeal of these exotic motifs was that they were historical and melodramatic. These design choices were also full of implied debauchery, which was very appropriate considering that Lobster Palaces were often establishments where men took their mistresses while their wives were tucked up at home on Long Island or the Upper East Side of Manhattan.

These interiors played directly into many of the American and European stereotypical views of the Middle East or Western Asia as exotic, sensual, and sexualized. They embodied the inaccurate but powerful Oriental fantasies that Americans and Europeans created in their art and literature starting in the 19th century. While these motifs were highly original, the service at Café de l’Opéra was subpar (the food often arrived cold) and the dress was too formal. It soon went out of business despite its unique décor.

The ziggurat, the stepped pyramid of ancient Western Asia, was a natural inspiration for New York’s skyscrapers. In his 1929 book The Metropolis of Tomorrow, the delineator and architectural illustrator Hugh Ferris noted the ziggurat (which he identified as Assyrian) embodied the New York zoning law of 1916. This law required that buildings have setbacks to allow light and air to circulate and reach the ground level. As a result, skyscrapers built in a step-pyramid style were incredibly popular. Ferris’s confusion suggests that archaeological accuracy and knowledge was not as important as in other receptions of ancient Assyrian art and architecture. That said, modern ziggurats dotted New York City’s skyline.

130 West 30th Street (1927–28)

Between 1927 and 1928, Cass Gilbert was hired to design a loft building at 130 West 30thStreet. While commercial lofts were designed with utility in mind, their exterior aesthetics could help distinguish them from other buildings. Hiring Cass Gilbert, who had designed the famous Woolworth Buildingand countless other masterpieces, was another way for the developer to attract tenants in the competitive landscape of Manhattan’s garment district. One Hundred Thirty West 30th Street had architectural setbacks, as required by the 1916 zoning law, which gave the building a ziggurat-like appearance. Glazed terra cotta friezes with mythical Neo-Hittite griffins and Syro-Hittite sphinxes decorated the building’s six setbacks. Lamashtu, a fearsome demon in ancient Mesopotamia, stood guard at some of the corners. These polychrome tiles and the setbacks differentiated the top of this building from its surroundings.

Over both the front and service entrances was the same terracotta relief of a hunting scene, with two male figures in a chariot shooting arrows at deer. The source for this relief is not those from the North-West palace of Ashurnasirpal IIat Nimrud, but rather, they are based on Neo-Hittite reliefs. The Louvre has a nearly identical scene from the kingdom of Milid (Malatya) in southeastern Anatolia and northern Syria dating from 1200 B.C.E. The ziggurat setbacks and Neo-Hittite sphinxes and griffins were unique in New York’s architectural landscape. The abstract aesthetic of the two-toned terracotta tiles and the building’s clean lines reflect the aesthetics of Art Deco, the artistic style that was emerging in the 1920s. Western Asian, Egyptian, and Minoan styles were already influencing Art Deco motifs and designs. The building feels undeniably more modern than skyscrapers that used historical styles.

Fred French Building (1927)

Ancient Assyrian art was used to decorate two other prominent New York City buildings: the Fred French Building and the Pythian Temple. Again, Assyrian motifs were intended to distinguish these buildings rather than to be archaeologically accurate. Between 1925 and 1927, the property developer Fred French erected his headquarters at 45th Street and Fifth Avenue. The diverse artistic traditions of ancient Western Asia inspired the Fred French building’s interesting top and setbacks, as well as bright polychrome terracottas and the decoration of the two lobbies and street-level façades.

Fred French’s in-house architect, H. Douglas Ives, worked with the firm Sloan & Robertson on the skyscraper. They adapted “Assyrian or Chaldean forms of ornament” for the flat surfaces of the building. For his design, Ives referenced the polychrome Tower of the Seven Planets, another name for the Tower of Babel, and observed that setbacks would permit planted terraces, like the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Ives called the style “Mesopotamian,” although this seems to have been a catch-all for the use of architectural and artistic forms from ancient West Asia.

Faience reliefs and setbacks, Fred F. French Building, New York (photo: Tony Hisgett, CC-BY-2.0)

Colored tiles, which always had an important place in thearchitecture of ancient Western Asia, figured prominently here. On the north and south façades of the building’s top, there are identical polychrome faience reliefs that center on rising suns, which symbolize progress, flanked by winged griffins, symbolizing watchfulness and integrity. Separated from the sun and griffins by two Corinthian columns are two golden beehives, each surrounded by five bees, which have symbolized thrift and industry since antiquity. The reliefs, with their glossy and polychrome finish, helped the Fred French building to stand out in New York’s Midtown skyline during the day. At night, the building’s crown was illuminated, adding to its prominence in the cityscape. The head of Mercury, the Roman god of commerce, appears on the building’s eastern and western sides.

The 5th Avenue Entrance, Fred F. French Building, New York (photo: Chris Sampson, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The building’s two lobbies and decorated façades are unique. The Fifth Avenue entrance featured lamassus and Pegasus (here mixing ancient Western Asian and Greek forms), as well as victory-like figures in the spandrels, that framed the door. The gilt-bronze doors are decorated with winged griffins, while Assyrian palmettes, lotus flowers, lions, chevron bands, merlons, winged bulls, and volutes adorned the Fifth Avenue lobby. Scaled-down double bull capitals inspired by the palace of Darius the Great in Susa were also included, as was a polychrome ceiling. The lobby and main entrance on 45th Street were similarly decorated.

The Pythian Temple (1927)

Designed by Thomas W. Lamb, the Pythian Temple (at 135 West 70th Street between Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues) is one of New York’s most original buildings and combines the artistic and architectural traditions of ancient Assyria, Babylon, and Egypt. Completed in 1927, the Pythian temple served as a lodge for the Knights of Pythias, a fraternal organization.

The main entrance is embellished with a golden inscription set against a black tile background and framed by two crowned asps, each with an ankh and two Egyptian-style vultures. Above the inscription there are polychrome terracotta tiles, evocative of Babylonian brickwork, and Egyptianizing plant motifs, where open and closed lotus leaves alternate. At the top, there was the inverted triangular, multi-color symbol of the Pythian Knights, flanked by two muscular griffins.

Four massive columns flank the main entrance on each side. The capitals are composed of two bearded, male heads with headdresses that derive from male figures in ancient Assyrian sculptural reliefs. At the east and west ends of the building, there are pairs of lamassus. The building was converted into condominium apartments in 1982, the middle section of the building was completely remodeled and most of the details were removed. The upper third is divided into three levels with setbacks and draws heavily on Egyptian architectural and sculptural traditions. It includes four seated, polychrome statues of pharaohs based on the statues from the famous site of Abu Simbel, which Ramesses II erected in the mid-13th century B.C.E.

Architecture inspired by ancient Assyria and ancient Western Asia did not become wide-spread in New York or the United States. Rather in the first three decades of the 20thcentury, architects and patrons used exotic Assyrianizing and Neo-Hittite motifs and architecture strategically to help their skyscraper, restaurant, lodge, and a loft to stand out in New York’s competitive urban landscape