Who are the warriors?

You may have seen them in an exhibition in a museum, as an image in a book, or perhaps even a replica as decoration in a house or a restaurant. The Terracotta Warriors—discovered in the tomb of Qin Shi Huangdi, the First Emperor of China—are one of the most recognizable images of Chinese heritage worldwide along with the Great Wall of China and the Forbidden City, and one of the most travelled exhibitions of Chinese art in the past century.

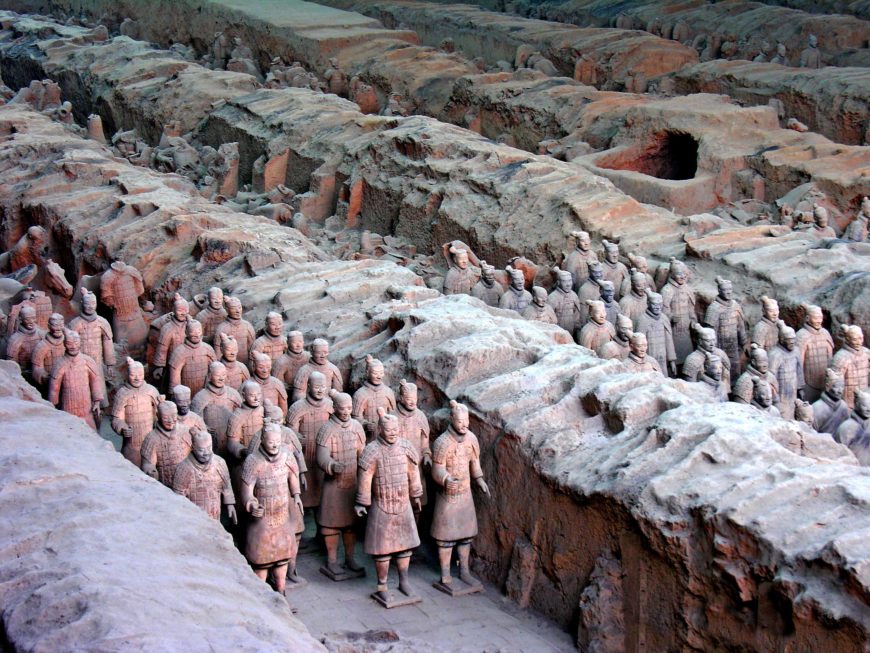

Looking at them from a distance in their original excavation site at Lishan (near the city of Xi’an in Shaanxi Province, China), the warriors look like a mass of identical figures or a giant’s set of toy soldiers. But up close, your impression of them changes—every figure seems to depict a unique individual, with different shapes of tunics, features, and hairstyles. Each soldier has a carefully rendered, bulky tunic, fastened with delicately tied knots, and strong gaze, making it seem as if you are confronting a person from thousands of years ago.

Some of the earliest scholars to write about the Terracotta Warriors describe them as portraits of the army of the First Emperor of China—replicas of actual soldiers who once lived—that the great 3rd-century state-builder, Qin Shi Huangdi, took to his grave.

But who are we really looking at? Are these truly portraits of soldiers from 3rd-century B.C.E. China?

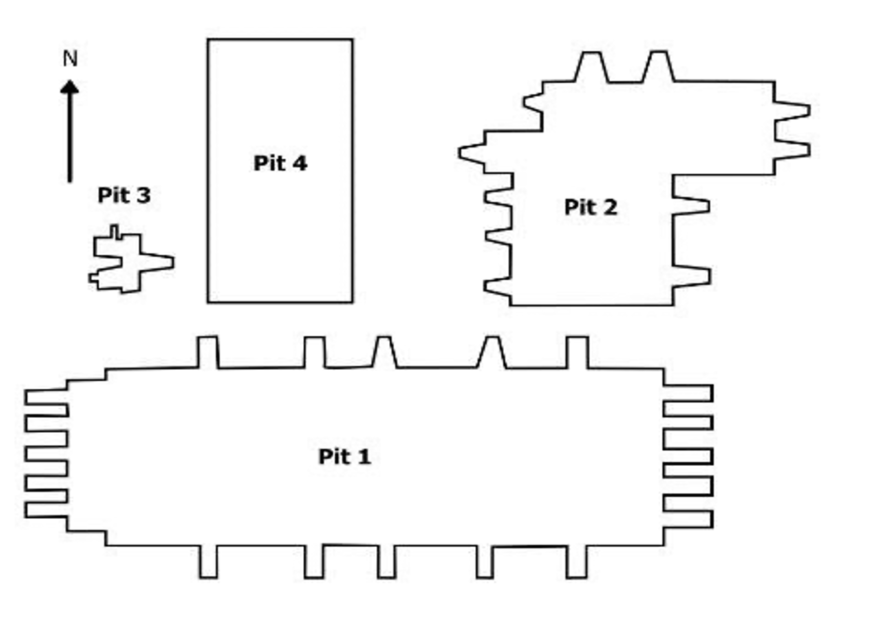

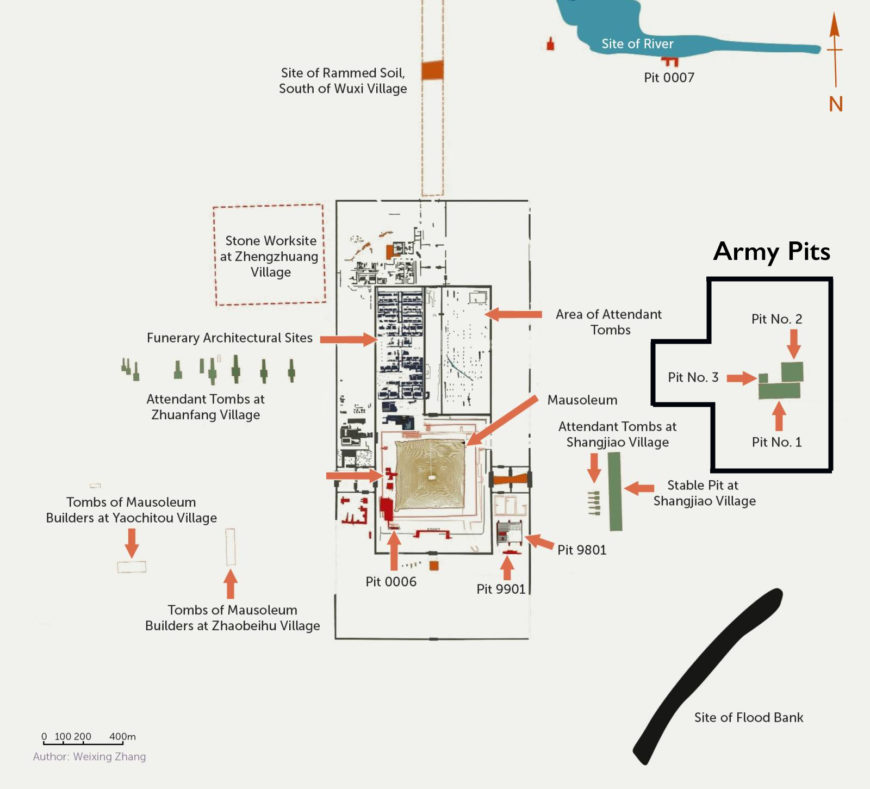

Plan of the tomb complex, Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi (diagram Weixing Zhang; modified by Alexandra Nach). The pyramid-shaped tumulus and the Army Pits, currently the site of the Museum of the Tomb of the First Emperor, are 1.22 km/0.75 miles away from each other.

The Army pits

The Terracorra Warriors were discovered accidentally in 1974 by farmers who, while digging for a well, unearthed several figures. Archaeological investigation soon revealed four large underground chambers (referred to by the archaeologists as “pits,” and these particular areas are referred to as the “army pits”), three of which contained shattered fragments of warriors made in terracotta. While the location of the tomb mound of the First Emperor had long been known, the terracotta figures were a dramatic departure from anything mentioned in the written record, or found in other tombs.

Pit no. 1 is the largest of the Army Pits. It is a large compartment dug into the earth, whose walls were reinforced with logs and covered by a wooden ceiling. Inside, it is split by earth embankments into 11 corridors containing soldiers lined up in battle formation. The massive pit was covered with a roof of heavy wooden beams, with five broad ramps on each side allowing workers to transport the terracotta soldiers into the lamp-lit tomb as they were being made. The panoramic view of the pit that we are presented with today, the result of removing the massive wooden beams composing the roof, is not one the workers (or even the Emperor) would have seen, but rather a curated experience enjoyed by the modern museum-going public.

While construction on the complex itself may have started as early as the future First Emperor’s ascent to the throne of the state of Qin in 247 B.C.E., the commonly accepted date for the start of construction of the Army Pits and the production of the terracotta warriors is around 221 B.C.E., when the unification of the Qin Empire was completed and the King of Qin declared himself the August First Emperor of China Sima Qian’s Record of Grand Historian records that at the time over 700,000 convicts and forced laborers were relocated to the tomb construction site. While some doubt this many laborers were used, archaeological evidence and our understanding of how the soldiers were made (see discussion below) support this timeline. It was this massive workforce that managed to dig out Pit 1, removing what is estimated to be around 70,000 cubic meters of earth, the equivalent of the carrying capacity of 5,500 modern lorries!

The roughly 1,900 terracotta infantrymen inside the pit are accompanied by 22 wooden chariots driven by four terracotta horses and manned by even more terracotta warriors. All the figures bear individually modeled armor, hairstyles, and headdresses that make every figure stand out as unique, and allow distinction between the ranks of the soldiers and their different roles in an army, from archers to infantrymen to charioteers. Though their armor is carefully modeled in clay, the weapons they brandished were real—the wooden components of each weapon have decayed, but the bronze spearheads, swords, and crossbow components were found by the archaeologists by the side of the soldiers. With the largest number of warriors (an estimated 6,000), Pit 1 is assumed to represent the main part of the army, reflecting the importance of infantry at a time when military dominance of a state depended on being able to assemble the largest numbers of warriors.

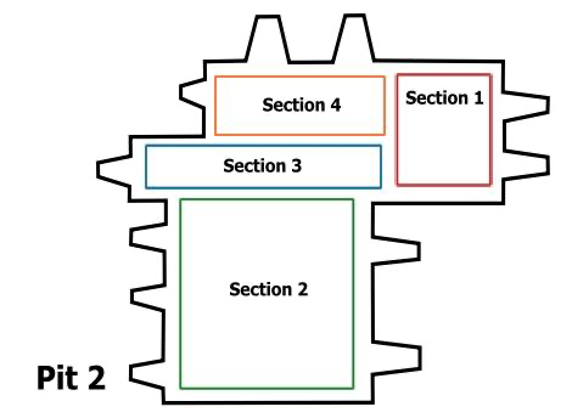

Pit no. 2

Overhead view of Pit 2, Army of the First Emperor of Qin, Lintong, China, Qin dynasty, c. 210 B.C.E., painted terracotta (photo: Aaron Zhu, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Pit 2 is split into four sections, and contains a wider mix of units. In section 1 on the eastern end, a double row of archers and spearmen stand in front of six columns of standing and kneeling archers split by embankments.

Front and back view of Kneeling Archer, Pit 2, Army of the First Emperor of Qin, Lintong, China, Qin dynasty, c. 210 B.C.E., painted terracotta

Section 2 on the southern end of the pit, on the other hand, contains primarily chariots (64 in total), each drawn by four horses and accompanied by a driver and two assistants.

Section 3 combines 19 chariots with 264 infantrymen as well as a small cavalry force at the rear.

Cavalryman and horse from Pit 2 (section 4), Army of the First Emperor of Qin, Lintong, China, Qin dynasty, c. 210 B.C.E., painted terracotta (photo: Maia C, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Finally, section 4 is primarily composed of cavalry, with 108 cavalrymen and their saddled horses headed by a group of 6 chariots. At the time of the First Emperor, the use of cavalry was a relatively recent innovation, only introduced to China in the 4th century B.C.E. Qin was one of the first states to establish a cavalry as part of their military force, a move that was instrumental to the unification efforts of the First Emperor. The cavalryman here is depicted with his saddled horse, dressed in a short armor jacket worn over a robe with pleated skirt designed to permit ease of riding.

Pit nos. 3 and 4

View from above of Pit 3, Army of the First Emperor of Qin, Lintong, China, Qin dynasty, c. 210 B.C.E., painted terracotta (photo: Zossolino, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Pit 3 is the smallest and most sparse of the three, and also the most puzzling. U-shaped, it houses 22 armored infantrymen in its north wing, and 42 in the south wing. While the military formations in the others face east, as if in preparation to be deployed away from the mound, the soldiers here face each other, as if expecting a commander to enter from the central chamber. Uniting the two wings is a central space housing a chariot that faces the main ramp to the east side (not pictured nor displayed due to its fragility). Unlike the chariots in the other pits, it was painted over with lacquer in vibrant geometric motifs and covered by a round canopy, all of which are signals that this was the vehicle of a member of the high command. Some scholars argue that the lavish chariot could have served as a symbol of the implied presence of the First Emperor as supreme military commander.

A fourth pit was excavated but contained no soldiers—perhaps not having been finished on time. What was the purpose of the vast assembled army in these pits?

An empire inside a tomb

Burying attendants in tombs close to the ruler, as well as burying important symbols of rulership like chariots or rituals broze vessels in royal tombs, had long been common practice in China before the time of the First Emperor. Often musical instruments and items of furniture were buried in compartments around the burial chamber, turning these compartments into “rooms” dedicated to individual activities. Modeling tombs as replicas of the houses of the living is an important feature of Chinese mortuary culture one that developed over long period time. Starting from around the 6th century B.C.E, replicas of household utensils and, occasionally, small figurines representing attendants to serve the tomb occupant in the afterlife, were increasingly found in tombs.

Left: Horseman, 5th–3rd century B.C.E., painted earthenware, unearthed at Tomb 2, Steel Factory, Xianyang, Shaanxi Province, 23.5 cm high, 17.5 cm in length (photo: mharrsch, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Cavalryman and horse from Pit 2, Army of the First Emperor of Qin, Lintong, China, Qin dynasty, c. 210 B.C.E., painted terracotta (photo: Maia C, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The tomb complex of the First Emperor is a major turning point in this development. The life-sized, intricately worked figures in the complex are a dramatic and abrupt departure from the small figurines of earlier tombs. Furthermore, rather than representing an article to be placed in a tomb, the First Emperor’s terracotta figures define the space around them, like actors on a stage, who through their costumes and actions allow us to imagine garrisons, stables, offices, and gardens.

Although we may not know the full context, the figures’ convey the bustle of activity and a variety of roles working under the emperor. They capture not only specific spaces around the imperial palace, like the Shanglin garden or a garrison, but also the staff and tools involved in running an Empire: from generals, to officials, to chariot drivers with their mighty chariots, to soldiers holding real weapons, to humble stable boys.

Earthenware figurines, before 141 B.C.E., excavated at the Mauseoleum of Prince Jing at Yangling, Shaanxi Province, between 30 and 60 cm (Han Yangling Museum; photo: Gary Todd, CC0 1.0)

While later tombs of the Han dynasty, including those of emperors, also contained ceramic figurines of different occupations engaged in little “scenes” mirroring everyday life, none of them were of the same size and artistic accomplishment as those in the tomb of the First Emperor. For example, the mausoleum of Emperor Jing, one of the largest Han imperial tombs, yielded over 50,000 figurines. However, they were only a third of the size of the First Emperor’s terracotta figures, and were rendered with significantly less detail in their clothing or individuating variety in their faces. The focus of these later tomb figurines also shifted away from officials and soldiers serving the Empire to household servants, attendants, and entertainers, as well as model granaries and herds of livestock.

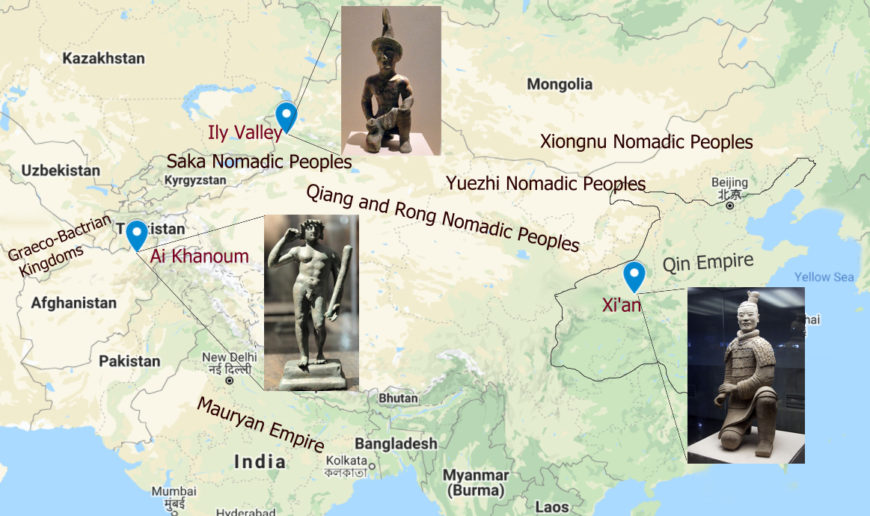

The reason for the sudden emergence of these life-sized, detailed figures has puzzled scholars for generations. As some have pointed out, prior to the terracotta warriors China lacked a tradition of large-scale sculpture in the round. When the human body was depicted in early Chinese art, it was mostly as small figurines with little attention to muscle definition in figures. Could the First Emperor, in his ambition to create a tomb like no other, have looked outside China, to Central Asia, where life-like Hellenistic Greek sculpture was used in tombs and temples?

Proponents of this theory point to mentions in the written records of the First Emperor casting twelve gigantic bronze sculptures (sadly all destroyed by the 4th century C.E.) in response to the appearance of “giants . . . in foreign robes” in the western provinces of the empire, interpreted by proponents of this theory as references to Hellenistic Greek sculpture. Archaeological finds in the western Gansu province and the Tarim Basin further west confirm that this area functioned as a corridor for trade between China and wider Eurasia. A kneeling bronze figure, depicted with a bare chest and what looks like a Greek Phrygian helmet, was excavated in the Ily River Valley in Xinjiang, confirming that bronze sculpture traveled along this early Silk Road.

Belt plaque of mythological creature, 3rd century B.C.E., gilt silver, North China, 12.7 cm high, 5.1 cm wide (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The nomadic peoples inhabiting the Tarim Basin and the Gansu corridor were major players in the movement of objects and technologies between Central Asia and China at this time. While the First Emperor often antagonized nomadic groups as part of his campaigns of expansion, the Records of the Grand Historian mention that he singled out certain nomadic groups as important trade partners. The presence of molds for making belt plaques in nomadic style, used to make elegant pieces such as one in the tomb of a 3rd century B.C.E. Qin smith from a suburb near Xi’an (now in The Metropolitan Museum of Art), is evidence of not only the lively trade between the Qin and the nomads, but also the willingness of Qin craftsmen to adopt foreign technologies.

Whether or not the makers of the First Emperor’s mausoleum were inspired by developments outside China remains a point of debate in the research on the tomb of the First Emperor, and it does not answer why the First Emperor and his tomb planners sought to include life-sized realistic sculptures so unlike anything that came either before or after. Some have seen this choice as a feat of grandomania, or the First Emperor’s wish to have nothing short of life-sized figures representing the grandeur of his empire. Other scholars have argued that this was part of the attempt to re-create the world of the living in the tomb: the more life-like the soldiers and other staff were, the more efficient they would be in serving the Emperor in the afterlife. In other words, the ability to render life-sized human and animal figures may have been seen as magical in itself, and their skillfully rendering and accurate detail acted as an enchantment.

This raises, however, a further question. If the tomb of the First Emperor mirrors his Empire, were his Terracotta Warriors also “portraits” of his living soldiers? Looking at how the terracotta figures were made sheds some light on this question.

Detail of lower part of incompletely reconstructed Terracotta Warriors, Army of the First Emperor of Qin, Lintong, China, Qin dynasty, c. 210 B.C.E., painted terracotta (photo: Tom Thai, CC BY 2.0)

Making the cast of the afterlife

Earthenware pipes, Qin Dynasty, Army of the First Emperor of Qin, Lintong, China, Qin dynasty, c. 210 B.C.E., painted terracotta (photo: IslesPunkFan, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Warriors’ faces are modeled in detail and with great care—but not their legs and feet which are plainly modeled. They have wide, bulky shoes and stocky legs shaped like rough cylinders that connect to the upper thighs covered by the coat.

There is a structural reason for the legs being rough and thick—they support the weight of the body, which the artists build from the bottom up. They also tell us something important about the way the soldiers were made—they are simple clay cylinders made in the same way that ceramic drainpipes were made in the tomb. Segments of Qin drainpipes were made by pressing rolls of clay into a cylindrical shape. In fact, many of the parts of the soldiers are constructed of simple parts made from pressing clay into molds and joined together like the drainpipes.

Detail view of the upper body of a warrior whose head has gotten detached, Tomb of the First Emperor of Qin, Lintong, China, Qin dynasty, c. 210 B.C.E., painted terracotta (photo: askaped, CC BY 2.0)

Warriors’ torsos and lower bodies, covered by armor and tunics, were made in one or two pieces by coiling as well as slab building. Using molds and applying additional bits of clay, the surface of each torso was worked into the armor and clothing detail.

Two halves of the mold used for the head of a terracotta warrior, Tomb of the First Emperor of Qin, Lintong, China, Qin dynasty, c. 210 B.C.E., painted terracotta (photo: Prosopee, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The arms, heads, and hands were produced separately, by pressing clay into molds, and later attached to the torso using clay slip. There was only a limited number of molds being used for every part of the body: two types have been identified for the feet, three for shoes, eight types of torsos, two types of hands, and eight types for faces.

Four faces of different terracotta warriors, Tomb of the First Emperor of Qin, Lintong, China, Qin dynasty, c. 210 B.C.E., painted terracotta (photo A: David Castor, CC0 1.0); B: Maia C, CC BY-NC 2.0; C: Gary Todd, CC0 1.0; and D: James H., CC BY-NC 2.0)

But then, why does each soldier look different? Each individual face had different types of mustaches and eyebrows attached, while the artisans subtly modified the details to create a sense of individuality, age, and sometimes even emotion. Fine lines were carved into the foreheads to show age (such as figures A and B above), while eyebrows were reshaped into frowns of concentration (such as figures C and D above). While some modifications conveyed personality, others established what category each soldier belonged to, like the “pheasant-tail headdresses” which identify B and C as generals.

After the figures were modeled, they were fired in a kiln and then painted with lacquer colored with strong pigments, like bright malachite, cinnabar, and azurite, alongside “Han purple.”

View of the soldiers at their discovery with visible traces of paint, Tomb of the First Emperor of Qin, Lintong, China, Qin dynasty, c. 210 B.C.E., painted terracotta (The Museum of Qin Terra-cotta Warriors and Horses, Xi’an; photo: edward stojakovic, CC BY 2.0)

Pictures of the soldiers at the time of excavation show how brightly colored they would have originally been; most of the paint dissolved shortly after excavation, though traces remain on the soldiers.

Making the warriors was not the work of a single artist working from a model, but the joint effort of a workshop team working with set molds. We know a lot about how such teams were set up. Each soldier is marked with an inscription that states the leading foreman of a team, their place of origin, and the name of their workshop.

A workshop stamp on a Qin-period tile (Museum at Qin Shihuang Mausoleum, Lintong; photo: Gary Todd, CC0 1.0)

Since some of the workshop names match the names stamped on tiles excavated in the First Emperor’s capital, we know that they were recruited from existing pottery workshops. The stamps allowed for a strict system of quality assurance, in which the foremen responsible for any fault in a product would be fined. It was this culture of strictly enforced standardization, already established in his home state of Qin, that allowed the First Emperor to re-shape the states he conquered into a centralized empire.

This modular, efficient production does not detract from the artistic achievement of the Terracotta Warriors. We may never know whether the workers modeled the features on actual soldiers who guarded the compound, on their fellow workers, or merely used their imagination, but they successfully imbued each figure with individuality. Like characters in a play, the soldiers and other terracotta figures were created specifically to enact a part of the world of the First Emperor in the afterlife. Even though we may not be looking at individual portraits of the soldiers of the First Emperor, the Terracotta Warriors successfully lead us to think that we are, and set them apart from ceramic tomb figures both before and after those of the First Emperor.

SOURCE

Alexandra Nachescu

Smart History

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Kesner, Ladislav. “Likeness of No One:(re) presenting the First Emperor’s army.” The Art Bulletin 77, no. 1 (1995): 115-132.

Khayutina, Maria. 2013. Qin: the eternal emperor and his terracotta warriors. Zurich: Neue Zürcher Zeitung Publishing.

Ledderose, Lothar. 2000. Ten thousand things: module and mass production in Chinese art.Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Portal, Jane, and Hiromi Kinoshita. 2008. The first emperor: China’s Terracotta Army. Atlanta, GA: High Museum of Art

Nickel, Lukas. “The first emperor and sculpture in China.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. University of London 76, no. 3 (2013): 413.

Wu, Hung. “On tomb figurines: The beginning of a visual tradition.” In Body and Face in Chinese Visual Culture, pp. 11-47. Brill, 2005.