Francis Bacon (1561-1626) was an English scientist and lawyer. Bacon was an instrumental figure in the Renaissance and Scientific Enlightenment. In particular, Bacon developed and popularised a scientific method which marked a new scientific rigour based on evidence, results and a methodical approach to science. He is widely considered to be the father of empiricism and the Scientific Revolution of the Renaissance period.

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) was an English scientist and lawyer. Bacon was an instrumental figure in the Renaissance and Scientific Enlightenment. In particular, Bacon developed and popularised a scientific method which marked a new scientific rigour based on evidence, results and a methodical approach to science. He is widely considered to be the father of empiricism and the Scientific Revolution of the Renaissance period.

Early life

Bacon was born 22 January 1561 near the Strand, London, England. Aged 12, he entered Trinity College, Cambridge where he followed a traditional medieval curriculum with most lessons conducted in Latin. Although he admired Aristotle, he was critical of Aristotle’s approach to philosophy (he called it ‘unhelpful’) and the scholastic tradition which was unquestioning in accepting past assumptions of the classic teachers, such as Aristotle and Plato.

Aged 15, Bacon travelled to the continent, spending time in France but also visiting Italy and Spain. He studied civil law and became acquainted with political realities, serving as part of England’s foreign ambassadors. On his travels, he delivered letters for high ranking English officials, including Queen Elizabeth I.

In 1579, the sudden death of his father meant Bacon returned home to London, where he began his practice of law at Gray’s Inn. With little or no inheritance, he was forced to borrow from family members to tide him over. Despite ill health, which dogged him throughout his life, Bacon was ambitious to serve his country, church and thirdly to pursue the truth – in philosophy and science.

In 1581, he was elected to Parliament as a member of Bossiney, Cornwall. He would remain a member of parliament (for different constituencies) for the next four decades. This provided a platform to help Bacon become a noted public figure and leading member of the government.

Bacon’s political views

Bacon was a liberal reformer. He supported the monarch within a parliamentary democracy. He supported reform of feudal laws and spoke in favour of religious tolerance. He was also an influential supporter of union between England and Scotland (which occurred 1707). He advocated the union on the grounds that a constitutional union would bring the nations closer together, promoting peace and economic strength.

His sharp intellect and grasp of issues saw him promoted to different posts, including Attorney General in 1594. He was also a skilful political operator, willing to flatter and beseech people of influence and power to help him gain favour.

However, after opposing Queen Elizabeth’s plan to raise subsidies for the war against Spain, he temporarily fell from favour and he struggled to find a position. His limited financial reserves came back to haunt him and, for a time, he was arrested for debt. However, he later regained the Queens trust and was part of the legal team which investigated charges against the Earl of Essex for a plot of treason against the Queen.

Bacon as Lord Chancellor

The ascension of James I, saw Bacon become one of the kings most trusted civil servants. He managed to mostly stay in favour with both the King and parliament – despite their estrangement over the Kings extravagance. Bacon was appointed Baron Verulam in 1618 and Lord Chancellor (the highest position in the land) in the same year. Bacon was the main mediator between the king and parliament during the tense years. By 1621, he was appointed to the peerage as Viscount St Alban. However, by the end of the year, his meteoric rise to the top of British politics came to an abrupt end as he was arrested for 23 counts of corruption. Bacon had fallen into debt, but also the charges were enthusiastically promoted by Sir Edward Coke, a lifelong enemy of Bacon.

Bacon argued the charges were promoted by political intrigue. Although he had accepted gifts, he claimed this was widely regarded as the custom of the day, and he never let it influence his decision. Writing to the king, he wrote:

“The law of nature teaches me to speak in my own defence: With respect to this charge of bribery I am as innocent as any man born on St. Innocents Day. I never had a bribe or reward in my eye or thought when pronouncing judgment or order… I am ready to make an oblation of myself to the King.”

— 17 April 1621

However, after a Parliamentary investigation, he admitted his guilt – perhaps hoping for a lenient sentence or perhaps feeling Parliament were determined to see his downfall whatever he said.

“My lords, it is my act, my hand, and my heart; I beseech your lordships to be merciful to a broken reed.”

Parliament though had little sympathy for Bacon and found him guilty. Bacon was fined £40,000, sent to the Tower of London and barred from holding future office.

After a few days in the Tower, he was released by King James and his fine overturned. But, his public fall could not be undone and Bacon would never return to parliament or public office.

Despite his fall from grace, Bacon responded with a prolific literary output; writing on a range of topics from science and philosophy to legal matters and Britain’s political situation. Bacon’s literary output and originality of thought were more remarkable given the backdrop of Sixteenth Century England. The religious and political tensions of the age had led to a period of limited philosophical inquiry. Bacon was an integral part of the English Renaissance, which saw a revitalisation of literature. Interestingly, Bacon has sometimes been suggested as the real author of the works of William Shakespeare, though this theory is not taken too seriously by scholars.

Scientific inquiry

It is this area of Bacon’s work that has been most influential. Bacon’s primary concern was to re-consider man’s approach to science. He rejected the assumptions of ‘innate knowledge’ and felt the duty of a scientist was to take a sceptical approach to any preconceptions, but only rely on the actual evidence and results of experiments. Bacon emphasised the importance of induction by elimination. Bacon also encouraged scientific progress through collaborative work.

Novum Organum (1620) was one of his most influential works, which expressed a new style of logic. Bacon advocated the use of reduction and empirical understanding. It rejected a more philosophical ‘metaphysical’ approach of the old sciences. Bacon invented the metaphor ‘idol’ to indicate how a man could be wrongly influenced by forces such as over-simplification, hasty generalisations or over-focus on meaningless language differences.

The importance of this scientific method is that it opened up the possibility for challenging all existing scientific orthodoxy. Bacon’s approach was championed by Voltaire, and it became a strong component of the French enlightenment. Modern science does not follow Bacon’s method in all detail, but the spirit of empirical research can be traced to Bacon’s revolutionary new approach.

Thomas Jefferson wrote: “Bacon, Locke and Newton. I consider them as the three greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception, and as having laid the foundation of those superstructures which have been raised in the Physical and Moral sciences”

Bacon was a hero to Robert Hooke and Robert Boyle the founders of the Royal Society.

Law

Bacon was prolific in suggesting reforms to English law. During his lifetime, few were accepted by the English legal system. However, after his death, some see Bacon’s general principles incorporated into modern legal systems, such as the Napoleonic Code and modern common law. The greatest contribution of Bacon was to place emphasis on the facts of the case, rather than a strict statement of legal precedent. Similar to his scientific empiricism, Bacon wanted the law to be more about the evidence and facts of the case, and not get caught up in obtuse legal precedents.

A criticism of Bacon is that he ordered five warrants for torture with regard to suspects accused of treason. Bacon argued torture could be justified, if necessary, to uncover plots of treason; though he did not admit it as useful for providing legal evidence.

Religion

Francis Bacon was a Protestant Christian, and his Christian faith was important to his outlook on life. However, his approach was broad-minded, seeing the role of rational scientific analysis. He generally advocated religious tolerance. He has been associated with the Rosicrucians – a mystical movement, which believed in a transformation of divine and human understanding. His work ‘New Atlantis’ expresses the ideals of a utopian community founded on spiritual laws and modern scientific rationalism. In this utopian land there is:

“generosity and enlightenment, dignity and splendour, piety and public spirit”

Bacon’s novel places a scientific institution, Solomon House, at the centre of the land, and remarks how the scientists seek to work in harmony with the Divine.

“We have certain hymns and services, which we say daily, of Lord and thanks to God for His marvellous works; and some forms of prayer, imploring His aid and blessing for the illumination of our labors, and the turning of them into good and holy uses.”

In 1609 he wrote De Sapientia Veterum (“The Wisdom of the Ancients”) which was an account of the hidden wisdom in ancient myths. It was one of his most popular books

“The most ancient times are buried in oblivion and silence: to that silence succeeded the fables of the poets: to those fables the written records which have come down to us.”

– Preface

It suggests Bacon’s sympathy to a more inclusive religious approach beyond the confines of modern Christianity.

Personal life

Aged 36, Bacon courted Elizabeth Hatton, but she broke off their relationship to marry Sir Edward Coke – a lifelong rival of Bacon’s.

Aged 45, Bacon married Alice Farnham, who at the time was just 14. The couple split, after disagreements over money. Bacon later disinherited Alice, after he discovered she had an affair with another man.

Aged 45, Bacon married Alice Farnham, who at the time was just 14. The couple split, after disagreements over money. Bacon later disinherited Alice, after he discovered she had an affair with another man.

On 9 April 1926, Bacon died from pneumonia. In an account by John Aubrey, (‘Brief Lives’) Bacon died after catching a chill conducting a scientific experiment – trying to stuff a fowl with snow to see if it preserved life. Writing his last letter to Lord Arundel, Bacon also mentions this incident:

“…As for the experiment itself, it succeeded excellently well; but in the journey between London and Highgate, I was taken with such a fit of casting as I know not whether it were the Stone, or some surfeit or cold, or indeed a touch of them all three.”

Bacon was a revolutionary figure in constitutional law, science and philosophy. He sought to advocate new ways of dealing with the world. His radical approach to fundamental questions of life and the world we live in were influential for promoting a different spirit – the new age of reason and enlightenment. Bacon sought a synthesis between a rational scientific approach, but also with a spiritual understanding of a just society.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan.

PUBLICATION: Omotoso Ibukunoluwa Omoniyi

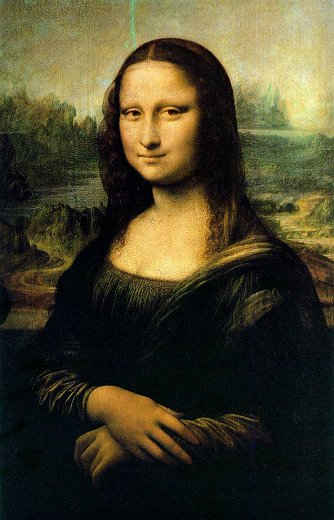

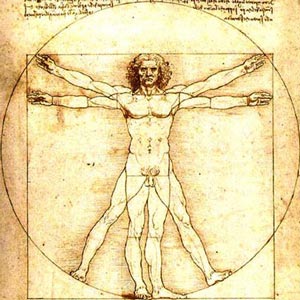

Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) is one of the world’s greatest thinkers, artists and philosophers. Seeking after perfection, he created rare masterpieces of art such as ‘The Mona Lisa’ and The Last Supper.’

Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) is one of the world’s greatest thinkers, artists and philosophers. Seeking after perfection, he created rare masterpieces of art such as ‘The Mona Lisa’ and The Last Supper.’

Living in the same time period as

Living in the same time period as